Here is the most detailed story yet from my recent talks on the links between wartime incarceration and the scourge of ICE abductions.  You should read the story by Kai Curry online at the Northwest Asian Weekly, but it conveys so much that’s important, and so much has changed since I first spoke on this in April, that I’ve shared it in full below. Thanks to the King County Library System and the Bellevue Library branch for centering We Hereby Refuse as their “One Bellevue, One Book.”

You should read the story by Kai Curry online at the Northwest Asian Weekly, but it conveys so much that’s important, and so much has changed since I first spoke on this in April, that I’ve shared it in full below. Thanks to the King County Library System and the Bellevue Library branch for centering We Hereby Refuse as their “One Bellevue, One Book.”

‘Never Again Is Now’:

Frank Abe links wartime incarceration to today’s immigration policies

by Kai Curry

NORTHWEST ASIAN WEEKLY

August 12, 2025

“Kind of a sour way” to spend a Saturday, Frank Abe said.

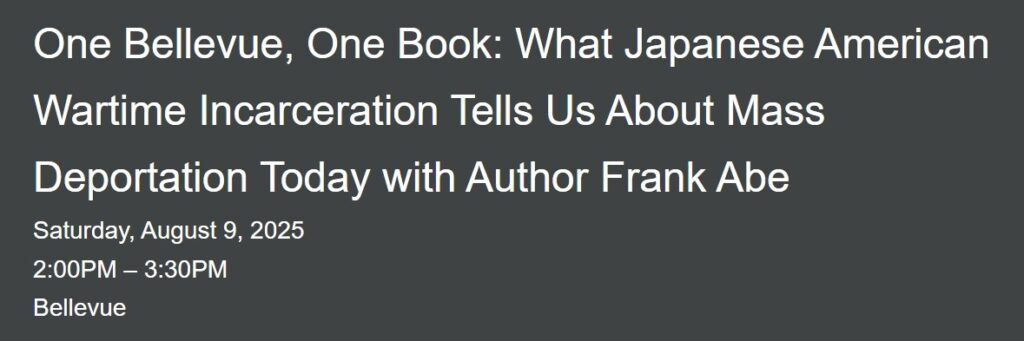

You’ve got that right. Depressing, frightening, angering is what it is. Yet it’s got to be said: The times we are living through now bear a disturbing resemblance to the times of the incarceration of Japanese people in the U.S. during WWII. There are few more qualified to say it than Abe, who gave a talk at Bellevue Library on Aug. 9, titled “One Bellevue, One Book: What Japanese American Wartime Incarceration Tells Us About Mass Deportation Today.”

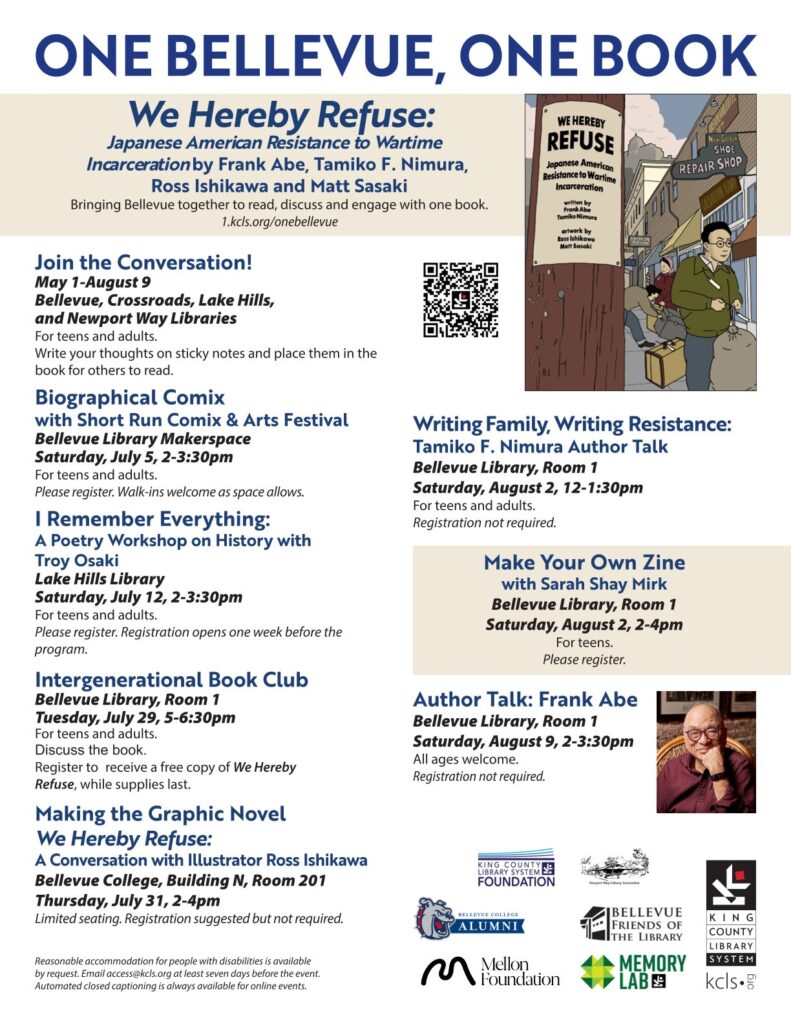

The talk was part of a series at the library surrounding the “one book”—“We Hereby Refuse: Japanese American Resistance to Wartime Incarceration”—which was written by Abe and Tamiko Nimura and illustrated by Ross Ishikawa and Matt Sasaki. Abe, who was instrumental in the late 1970’s in starting the Japanese American Day of Remembrance for those incarcerated, and for those hard times, began by laying out the basic structure of the book and its characters.

And by “characters,” we mean real people who suffered arrest, interrogation, and incarceration during the crackdown against anyone of Japanese ethnicity, alien or non-alien, during WWII. “We Hereby Refuse” flawlessly (but not effortlessly, as Abe’s research and writing was painstaking, by his own admission) interweaves the true stories of three people: Jim Akutsu, Hiroshi Kashiwagi, and Mitsuye “Mitzi” Endo. Akutsu, famous for being the inspiration behind the book “No-No Boy” by John Okada (about whom Abe wrote a biography), refuses drafting into the U.S. military from Camp Minidoka as long as he is being labeled an “enemy alien.” Kashiwagi, sadly, under pressure while at Camp Tule Lake, signs a loyalty oath to Japan and renounces his U.S. citizenship so that he can stay close to his family (and later strives to reverse this). Endo became famous for taking her case of unlawful arrest and imprisonment to the U.S. Supreme Court. In 1944, the Court handed down the decision in Endo’s case that led to the cessation of restrictions on Japanese Americans and the closure of the incarceration camps.

During his talk, Abe explained the history of this shameful period in U.S. history, along with the parallels he sees in the way the current administration is behaving, particularly on the subject of deportations. He bemoaned that, in part due to the constant onslaught of new, troubling actions by the president and his supporters, the American public quickly forgets who has “disappeared,” what happened to them, and whether they come back or not? Abe spoke of Mahmoud Khalil, a student protester at Columbia University who is now seeking restitution for the time he spent in jail. (It should be noted that these deportations, this jail time, is not pleasant; people are being kept in deplorable conditions both in the U.S. and in prisons abroad.) Khalil has actually mentioned the case of Endo as a precedent for his current situation. Khalil wrote about Endo while he was incarcerated by ICE and said, tellingly, “The rhetoric of justice and freedom obscures the reality that, all too often, America has been a democracy of convenience.”

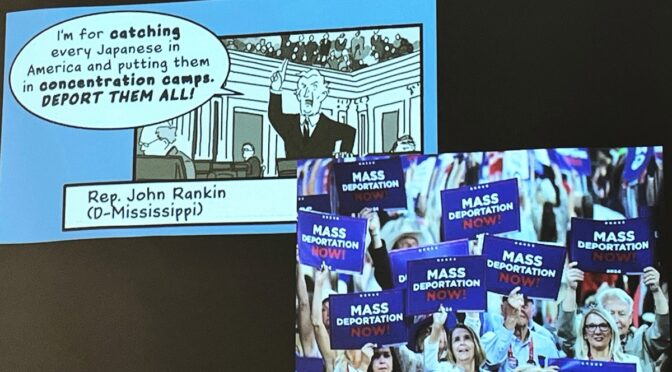

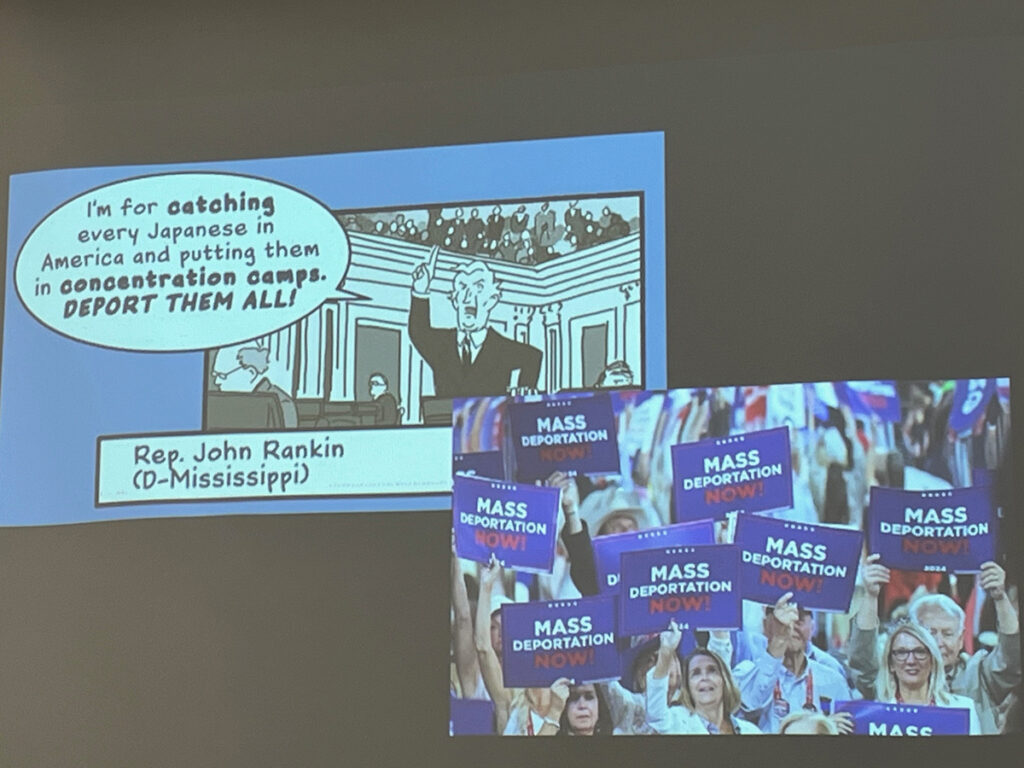

So many parallels, it is downright chilling. Sometimes exact wording is being used by politicians today that was used during WWII, Abe pointed out. Why were approximately 120,000 people incarcerated with no evidence of political activity, no evidence of wartime espionage, and no due process? Why were they taken away from their homes, their jobs, between 1942 and 1946? No reason except racism. And the perverted rationale that there “might be” a reason. “The very fact that no sabotage has taken place to date is a disturbing and confirming indication that such action will be taken,” said the Commanding General of the Western Defense Command and the Fourth Army sent in 1942 in a memorandum to the Secretary of War. How could someone say something so nonsensical, you might wonder? How can the fact that there’s no evidence be evidence?

Surely, no one would say that today, right? Wrong. On the screen, Abe put two statements, the one mentioned above, and a statement this year by ICE Acting Field Office Director of Enforcement and Removal Operations Robert Cerna about deportation of alleged gang members: “While it is true that many of the [Tren de Aragua gang] members removed under the AEA do not have criminal records in the United States, that is because they have only been in the United States for a short period of time. The lack of a criminal record does not indicate they pose a limited threat.” We are just supposed to take it on faith that they have reasons.

Yet history tells us differently. History tells us there very likely aren’t good reasons. The above is one of many examples of history repeating itself. For some, it seems, the repetition is a gleeful occasion; for everyone in the room at Abe’s talk, the repetition is a travesty.

“Never again is now,” Abe and others reminded those present of the phrase used by those who resist, today, the recurrence of those traumatizing days, and years, for Japanese Americans incarcerated during WWII. Meanwhile, a mural stating this very phrase on a wall in Seattle’s Chinatown-International District was vandalized this very month, and the second time this year.

What causes this kind of hate, this racism? Fear of others, Abe theorized. Yet maybe it’s all just a distraction tactic, he and audience members speculated. A distraction to keep the American public turned away while the “oligarchy” lines their pockets. Maybe our leadership is purposely “stoking our basest fears,” Abe suggested, while they transfer trillions to their bank accounts. Either way, it’s U.S. citizens who face the consequences. It’s likely to only get worse, Abe projected. So what can we do? “I’m just a writer,” Abe humbly answered. So what he does is write. Others should do whatever they can and with which they are comfortable.

“Talk to your neighbors, talk to each other,” resist the push of the administration to isolate us from each other. Vote? There’s some skepticism attached to that; and bewilderingly, even when a court insists the president desist from some action, he doesn’t—that’s one thing different from the 1940s.

“Do what you can,” said Abe. Speak in your own way, he said, against what is basically bullying. Before the talk began, Abe, who has a deep resounding voice that reverberated around the room even without a microphone, congenially discussed the Mariners (he’s a big fan) and Ichiro Suzuki’s retirement with those in the front rows. Due to his constant advocacy and activism, Abe knew multiple people in the audience. In spite of his humble bearing, he has been and continues to be someone that the community looks up to, and a force of resistance in trying times.

Kai Curry can be reached at [email protected].